EARS DON'T LIE

Ear Analysis Has a Long History

by Joelle Steele

Before the science of fingerprinting came into common use in the early 20th century, the ears were also used to identify people. A man named Alfred Victor Iannarelli developed the forensic method of ear analysis for the purpose of identifying people in 1949. His book, "Ear Identification," (1989, Parmount Publishing Company) is out of print, but it thoroughly describes his system. The Iannarelli System of Ear Identification, relies on biometrics, the measurement of body parts, in this instance, the ear in particular. Iannarelli has impressive credentials in law enforcement as well as extensive experience in studying thousands of ears and making identifications based on ear analysis and comparison. Until his death in 2015, he was still active as a Consultant in Forensic Identification and Police Administration in the San Francisco Bay Area of California.

Before the science of fingerprinting came into common use in the early 20th century, the ears were also used to identify people. A man named Alfred Victor Iannarelli developed the forensic method of ear analysis for the purpose of identifying people in 1949. His book, "Ear Identification," (1989, Parmount Publishing Company) is out of print, but it thoroughly describes his system. The Iannarelli System of Ear Identification, relies on biometrics, the measurement of body parts, in this instance, the ear in particular. Iannarelli has impressive credentials in law enforcement as well as extensive experience in studying thousands of ears and making identifications based on ear analysis and comparison. Until his death in 2015, he was still active as a Consultant in Forensic Identification and Police Administration in the San Francisco Bay Area of California.

Law enforcement forensics experts, such as those working for the FBI, have known about Iannarelli's system and "ear biometrics" for a long time, and they still analyze ears when comparing photos of known criminals with photos of suspected criminals who have undergone facial damage or plastic/reconstructive surgery, because ears are rarely modified surgically — they heal far too slowly and often very unattractively. Ear biometrics are still used today as a back-up to fingerprinting when a criminal has had his fingerprints removed, or in identifying bodies when the fingers have been removed or destroyed. Remember, not everyone has a DNA profile in a database!

Ear biometrics is also used by facial features experts in identifying people in photographs. Before I compare anything else, I look at are the ears - if they are visible - in the photos. If the ears don't match from one person to the other, then the two photos cannot be of the same person. There is no reason to waste time examining the faces further. In addition to being unique to each person, ears are also reliable for comparisons of people because they do not change with variations in the facial expression (i.e., when you smile or frown).

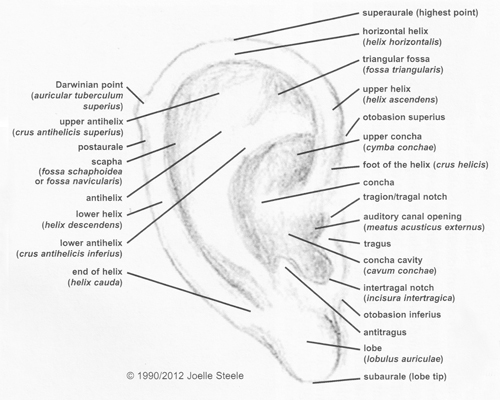

OUTER EAR TERMINOLOGY

If you look at various diagrams of the parts of the ear, you will find that the names vary and that some parts are not labeled at all. The ear diagram below is correct and complete, showing all 25 traits. However, there can be other visible ear traits when the ear is viewed from different angles, such as how far the ears protrude from the head and how they align with the facial features.

THE 25 ANATOMICAL PARTS OF THE EAR

As for the names of the ear parts, it helps to understand some of the Latin names, even though they are anglicized somewhat in the diagram. For example, the outer ear is called the auricula, auricle, or pinna. Pinna is from the Latin "penna" meaning leaf-shaped or wing-shaped, and auricula and auricle mean "ear." The word "concha" means shell-shaped and is the name for the bowl-shaped area in the central part of the outer ear. The "meatus" is the opening or passage to the auditory ("acusticus") canal of the inner ear. The word "helix" is from the Latin/Greek for "spiral" and refers to the folded rim of skin that runs along the outermost edge of the ear. The Latin word "crus" (not "crux," which appears erroneously in some ear diagrams) means "leg" or "leglike." Its plural is "crura." The words "fossa" and "scapha" are Latin terms that refer to small indentations or depressions, with the scapha being the narrower furrow-like form of the two. The "tragus" is a Latin form of the Greek word "tragos," meaning "goat," and it refers to the part of the ear that grows hair as we age. Lastly, the word "tubercle," which usually refers to one of the four Darwinian points found on about 10-25% of all ears, is a small, rounded protuberance. The other Darwinian points as defined by Iannarelli are the nodosity (node, nodule), enlargement, and projection.

Other Latin terms modify the names of some of the ear parts. For example, "superius" means "highest"; "inferius" means "lowest"; "descendens" means "descending"; "ascendens" means "ascending"; "triangularis" means "triangular"; "externus" means "external"; and "horizontalis" means "horizontal."

ANALYZING THE EARS

When analyzing and comparing ears, look at how the ears line up with the features of the faces, the jaws, and how big the ears are in proportion to the heads. Look at how far they stick out from the head and where they line up with the features of the face. However, before you start aligning ears with facial features, you must first determine whether the photo was taken from an angle that is either higher or lower than the person. If it is, the ears will not be aligned correctly with the eyes or any other feature for the purposes of an accurate comparison. You'll need to rely on other individual ear traits for comparison, if visible.

Look at the shape and the curves and lines of the ears of each person as shown in the illustration above. These formative structures of the ear are entirely unique to each person. Ears may be round, oval, rectangular or triangular, and variations of those shapes. The helix of the ear, which forms the entire outer rim of the ear, will never be the exact same shape in any two people, not even people who are closely related (Iannarelli found some ear resemblances among siblings of the same parents, but not between a parent and child). The intertragal notch may be higher and/or wider from one person to the next. The concha area can be deep or shallow, wide or narrow. So always look very closely at all of these details when they are visible in a photograph.

Also look at the lobes to see if they are attached or unattached (free), and if they are unattached, whether they hang close to the head or stick out. Lobes can be narrow, wide, flat, creased, pointed, squared, etc. Also look for a Darwinian point, that little nodule on the outer edge of the helix, and be sure both people have it in the exact same place. It's a hard little point to see in most photos, but if it's there, you should be able to find it.

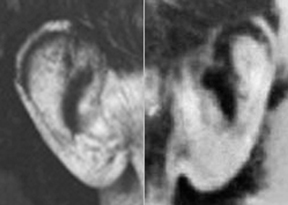

Ears can protrude (stick out) from the head to varying degrees, or they may be set close and flat to the head, some set so deeply that the concha is almost recessed into the head. Ears may be positioned at different levels on the head — normal being when the upper rim of the helix is even with the eyebrow. Also note that on any given head, one ear may look different than the other or it may be placed a little higher/lower on the head. No person is ever completely symmetric. Examples of this are found in the ears of Frank Sinatra and Abraham Lincoln..

ABOVE: The two ears above are those of Abraham Lincoln. His ears did not match each other in appearance.

EAR GROWTH

Ears grow with age. Iannarelli's research indicates that the human ear reaches its structural maturity at 4 months of age, and that it then grows in size, but is not altered in form/shape, up until about the age of 20, after which it gradually lengthens, mostly in the lobe, from about 7mm to 13mm until age 60-70. According to a 1995 British study with several other physicians and hundreds of subjects aged 30-93, James A. Heathcote, MD concluded that our ears grow at an average rate of about .22mm (.01 inches) per year.

Heathecore's study was confirmed by a Japanese study of 400 people in 1996. While average growth rates vary from person to person and may vary during different stages in a person's life, we can assume that an individual with a 2" long ear at age 30 would, by age 80, have achieved about a 25% growth rate, resulting in about a 2-1/2" long ear.

Since the growth of ears does not affect their basic design structure and form, we can use the ears for comparison to identify a person in a photo no matter what their age.

SUMMARY

If the ears are visible and clear in a photo, you are truly in luck, because they are one of the best — if not the best — traits to compare that will help confirm or rule out a match between any two faces.